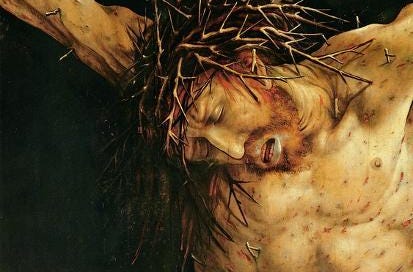

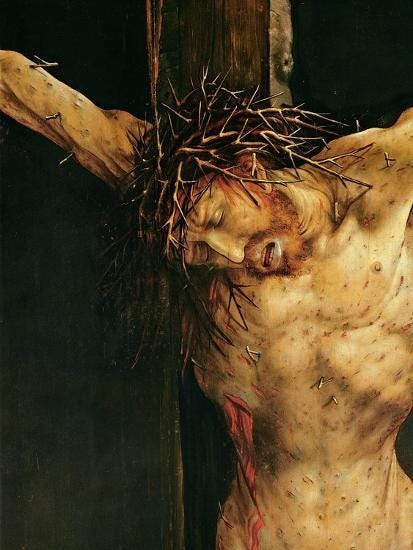

The Isenheim Altar piece, of which you can see a detail here, is as striking as it is disturbing. Surrounding the dead or dying Jesus—his body still has color, but his lips and feet have turned palid—are his disciple John, who holds Jesus’ distraught mother; Mary Magdalene, who looks to be begging in prayer; an uncomfortably serene John the Baptist, who points to Jesus on the Cross; and at the Baptist’s feet is a little lamb, leg around a small cross, blood pouring out of a wound in his neck into a golden Eucharistic chalice. The center of the piece, obviously, is the crucified Jesus.

The piece strikes me because of the grotesque nature of the gaunt body of Jesus full of cuts and thorns, the small details like the colorless lips, that the blood flowing from Jesus’ side looks like a banner, or that Jesus’ body looks more disease ridden than beaten. But what grabs me the most, what holds my attention are Jesus’ nailed hands, twisted up in agony.

There’s an absurdity in all of this. Just a few days before, Jesus rode into Jerusalem on a donkey, fulfilling the ancient prophecy (Zech. 9:9-10) that spoke of the deliverance of God’s people from the bondage of foreign powers. Or so it seemed. Today, when that foreign power asks what they want to happen to this supposed King of the Jews, the crowds that welcomed him now cry, “Crucify him!” It’s the same absurdity that fills all of life, the shadow that hovers ever present on the brightest and best of days. It’s the absurdity that causes disciples to run away from Jesus, sometimes forever. It’s the doubt that asks, “Did God really say…?” Pilate felt it too, standing before this sweaty, stinking, torn pile of flesh.

Then Pilate entered the headquarters again, summoned Jesus, and asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” Jesus answered, “Do you ask this on your own, or did others tell you about me?” Pilate replied, “I am not a Jew, am I? Your own nation and the chief priests have handed you over to me. What have you done?” Jesus answered, “My kingdom is not from this world. If my kingdom were from this world, my followers would be fighting to keep me from being handed over to the Jews. But as it is, my kingdom is not from here.” Pilate asked him, “So you are a king?” Jesus answered, “You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.” Pilate asked him, “What is truth?”

John 18:33-38

The truth that Pilate could feel but not see, like humidity on a hot summer day, that he could name but not believe, was that this crushed man, Jesus, was indeed a king. We’ve all stood where Pilate stood, and asked his question, or some version of it -

Is this real?

Do I believe in God?

Why did that happen?

What is truth?

We’ve all had to look at the bloody mess in front of us that was once a man and ask, “Are you the king of the Jews?” And we’ve all had to wrestle with his answer, “You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.”

What the Isenheim Altarpiece puts on stark and disturbing display is the truth that, if God is transcendent, it’s not the transcendence of distance but of presence. He is present with us in a body because God, in the mystery of the Trinity, is a man. When the crops fail, when the friend dies, when the pain flares up again, when the sparrow falls, it is all marked on the body of our God, Jesus Christ.

It’s our own absurdity too. The fact that we lie to those we trust, that we take what’s not ours because we feel we deserve it, that we resent those who love us, that we hoard our money and possessions, that we have not loved our neighbors as ourselves. Or, to use that old religious word, that we sin. All of that, too, is marked in the body of our God, Jesus Christ.

The absurdity is real, and belief in Jesus Christ doesn’t ask that we deny the absurdity. In fact, believing in Jesus Christ means we embrace the absurdity, and instead of hiding from it, we dive headlong into it.

Jesus embodies all of life’s absurdity and it goes down into the ground with him like a seed planted in good soil. In the spirit of the season, we will wait to see what happens to the seed, but for now, let us meditate on the bloody and dying body of Jesus, who today gathers all our loss and pain and sin, all our absurdity, into his body and takes it with him up to his throne, the Cross.