2018 me would never believe that 2024 me would say a Christian not only can, but (probably) should vote.

There were several factors that led to me being a self-described “conscientious non-voter,” but among them was the realization that no political party in the United States cared two shits about the Kingdom of God. I realized this sometime before Pres. Obama’s second term while, during the campaign season. I was part of a Christian movement that had long proclaimed that faithful Christians could never vote for a pro-choice candidate. We wore red bracelets with the word “LIFE” on them and made public oaths to never vote for a pro-choice candidate. This was an easy stance to hold in the days of George W. Bush, when to be Republican was to be pro-life, but when Mitt Romney, who had a long history of pro-choice policies and opinions, was the leading contestant against Barack Obama, suddenly the water became muddied.

I was already questioning the validity and righteousness of Christian voting. I had watched Bush turn a national tragedy into an excuse to war hawk his way through the Middle East1 at the expense of thousands and thousands of lives from the United States, Iraq, and Afghanistan, many who were civilians. It already didn’t make sense to me that we could vote against someone who would “murder babies,” but vote for someone who would, without remorse and in vain, send our soldiers to their deaths and murder innocent people overseas. I was already on the edge of becoming a non-voter. When Romney took the lead and the choice was between two pro-choice candidates, I was eager to see how my leaders would respond. Would they keep their “solemn commitment,”2 and encourage us to do the same?

The answer was a simple but undeniably loud, “No.”

I knew I would never vote again, or at least so I thought. My decision wasn’t simply about abortion, it was about the whole mess. It was coming to terms with the fact that the Republican party had seduced evangelicals and other conservative Christians, promising them the next best thing to heaven this side of eternity. It was the realization that the parties wanted votes, both both capitulating to money, and that capitalism was the soil from which the poisonous fruit of our politics grew. Voting may be a privilege, but it is also a choice, and it was a choice I was unwilling to make. I held this conviction staunchly for several years, arguing with my wife, my family, my friends, my coworkers, and my church family. No one could convince me that to vote for a politician was somehow righteous, and no one could convince me there was such a thing as a “lesser of two evils.”

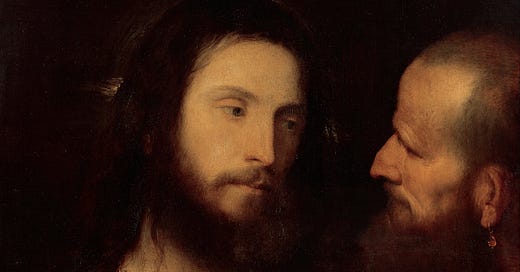

Enter Dietrich Bonhoeffer

In 2011, I read a biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. I was fascinated by this man who would hold his convictions firm in Nazi Germany, who could think so subtly and profoundly, who would return to Germany from the US at the risk of his own life in order to struggle with the faithful Christians there. After the biography, I read Bonhoeffer’s Discipleship which, without exaggeration, changed my life. He quickly became and remains my biggest hero, and he influenced my theological life and thought more than anyone.

Without a familiarity of Bonhoeffer’s writings and thought, his ethics—and therefore his politics—can be confusing. This was a man who, though he vehemently opposed Hitler, could tell his seminarians they could fight for Germany in WWII if they felt it was where God was leading them, but they could also conscientiously object and work against Hitler and his regime if that was the direction God led them. He could be a committed pacifist, and without giving up his ethics, work for the resistance movement that sought Hitler’s assassination. This was possible because he believed Christians were called to live, not by rules or principles, but in “simple obedience” to Jesus.3 This doesn’t mean we’re not bound by obedience to Jesus’ commands in something like the Sermon on the Mount. In fact, the Sermon is the heart of his book, Discipleship.4 Rather, the Sermon teaches how to follow Jesus, and when the moment of decision comes, we must take action to obey Jesus in the way the moment demands.

An easy example of this comes from the WWII era, a time of ethical dilemmas that Bonhoeffer was well familiar with. If Hitler is exiling, persecuting, and murdering Jews, and a Jew comes to hide in your house, what will you do when the Gestapo shows up at your door asking if there are Jews in your home? For Christians,5 the answer seems obvious. Lie to the SS officer. It seems obvious, but Bonhoeffer will not let us off the hook so easily.

One of the governing ethical philosophies of the time was developed by the philosopher Immanuel Kant, who maintained that moral duty would require us to tell the truth, because telling a lie is wrong. Therefore, when the SS officer shows up at your door and asks if there are Jews hiding in your home, you should say yes, because that is your moral duty. You are not responsible for the actions of the Gestapo, only yours. Even if the officers march the Jewish family, children included, and shoot them in the street, you should not feel guilty because you followed your moral duty to tell the truth. Kant’s moral vision was rigid, but it created an opportunity for you to live without guilt. Bonhoeffer’s ethics, on the other hand, were not as rigid—one could, and perhaps should lie to the Gestapo—but they simultaneously demanded more of the Christian.

Throughout his works, but especially in his Ethics, Bonhoeffer talks about the Christians responsibility to Stellvertretung, a German word meaning “vicarious representative action.”6 Bonhoeffer developed this idea deeply, but at its core he meant that Jesus’ ethical call to his disciples was “taking responsibility for others…being and acting for them and with them, stepping into their place.”7 They are called to that because this is precisely the way God has entered into the human situation in Jesus Christ. Of this, Bonhoeffer says,

Jesus’ concern is not the proclamation and realization of new ethical ideals, and thus also not his own goodness, but solely love for real human beings. This is why he is able to enter into the community of human beings’ guilt, willing to be burdened with their guilt… A love that would abandon human beings to their guilt would not be a love for real human beings. As one who acts responsibly within the historical existence of human beings, Jesus becomes guilty. It is his love alone, mind you, that leads him to become guilty. Out of his selfless love, out of his sinlessness, Jesus enters into human guilt, taking it upon himself.8

Another way to say this is that when God decided to save humanity, he did not do it apart from us but entered into our world, into our situation, so closely that the Son became a human being. As a human being, Jesus did not have a different kind of humanity. Our flesh was his flesh. His flesh was sinful flesh like ours. This isn’t to say Jesus made sinful choices, but that by becoming a true human being, he took on human guilt, and in that way took responsibility for us and saved us from our guilt. In Romans 8:3-4, St. Paul explains it this way:

For God has done what the law, weakened by the flesh, could not do: by sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh, and to deal with sin, he condemned sin in the flesh, so that the just requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit.

The rub in Bonhoeffer’s ethical ideas, over against Kant’s and our own inclination to preserve ourselves from guilt, is that he maintained Stellvertretung, acting with responsibility toward others and on their behalf, meant that we would never be guiltless in our actions because, like Christ entering into our world for us, our actions take place in this sinful world and are always tainted by sin, but we could maintain our confidence before God because it is he who called us to live this way and it is he who saves us through his Son Jesus.

What does this all have to do with voting? In 2020, I took a deep dive into Bonhoeffer’s life and works while working on my theology degree. Up to that point, I had not voted because, as I said, I believed that to vote was to participate in a sinful institution. I did not really believe there was a “lesser between two evils.” I could not bring myself to cast my lot in with Babylon. I believed that the appropriate prophetic act was to stand apart and critique from the outside.

As I read Bonhoeffer, I could feel myself being challenged by him. The intensity and chaos surrounding the Trump presidency was ramping up through the COVID pandemic and the protests following the murder of George Floyd. The issues of race, immigration, misogyny, patriarchy, and so many other things were confronting me over and over again as I sat quarantined in my home. I could hear Bonhoeffer asking me to take my place in the world in which God placed me. He was telling me I should vote.

The catch was that he wasn’t asking me to change my mind about our political system. There was no lesser evil. My vote would be my participation in an evil system unconcerned about the Kingdom of God or the way of Jesus. To vote for either major party or even a third party would be to cast my lot in with Babylon. I would not remain guiltless, but it was my calling as a disciple of the incarnate Jesus. To vote would be to sin, but Jesus was calling me, through Bonhoeffer, to sin boldly.

Voting is sin

It’s not uncommon these days to hear someone say something like, “You can’t be a Christian and vote for…” or, “I’m voting for… because I’m a Christian.” These phrases are used as an attempt to strongman someone into voting for the person’s candidate of choice. They’re not honest arguments, nor or they effective. People have several reasons why, as a Christian, they must vote for this person or why they cannot vote for that person, but if often, boils down to a few points around abortion, immigration, and either a fear of or desire for socialism. The political theology, if I can call it that, I was raised on hinged on abortion and the pro-life vote. How could a Christian vote for a presidential candidate who was willing to murder babies? What was a simple question for many in the churches I came of age in was, in my eyes, an unintentional revelation of what kind of murder Christians in the US were okay with. Don’t kill babies in the womb, but kill them in Afghanistan. That cut across in the opposite direction as well. Why oppose the war in the Middle East if you’re okay with killing babies in the womb?

As time has progressed, the way people answer questions like these is getting more cold hearted. I see a growing apathy toward the opinions of the political other, and think it has more to do with our unwillingness to hear and the ever-present reality of social media than it does with how policies actually work. So now we watch Palestinian children die with no sorrow in our heart and own the Conservatives with crass statements about abortion.9 And still, the questions remain.

How can a Christian vote for a person in favor of abortion?

How can a Christian vote for someone who will support war in the Middle East?

How can a Christian vote for a party that is hell-bent on protecting the “rights” of corporations over those of living human beings?

How can a Christian vote for a party that denies parents the responsibility to walk with their children through questions of gender and sexuality?

How can a Christian participate in the Babylonian system we call the United States of America?

Which party—Democrat, Republican, or something else—is the correct party to vote for as faithful Christians?

We’ve been trying to figure out which party is right or wrong, and we’ve missed our calling to something deeper as disciples of Jesus Christ. Bonhoeffer has advice to give, and though he was thinking of Christian ethics more broadly, I think his words carry wisdom for us as we go to the polls in a week.

Those who wish even to focus on the problem of a Christian ethic are faced with an outrageous demand—from the outset they must give up, as inappropriate to this topic, the very two questions that led them to deal with the ethical problem: “How can I be good?” and “How can I do something good?” Instead they must ask the wholly other, completely different question: what is the will of God?…All ethical reflection then has the goal that I be good, and that the world— by my action— becomes good. If it turns out, however, that these realities, myself and the world, are themselves embedded in a wholly other ultimate reality, namely, the reality of God the Creator, Reconciler, and Redeemer, then the ethical problem takes on a whole new aspect. Of ultimate importance, then, is not that I become good, or that the condition of the world be improved by my efforts, but that the reality of God show itself everywhere to be the ultimate reality. Where God is known by faith to be the ultimate reality, the source of my ethical concern will be that God be known as the good, even at the risk that I and the world are revealed as not good, but as bad through and through.10

In short, what Bonhoeffer is saying is that when we consider ethics we often are asking the question, “How can I do or be good?” or, “How can I make the world good?” When we ask those questions, we’re making ourselves the center of reality. Our ethical questions and actions should instead be focused on revealing the good God who reconciles us to himself through Jesus Christ. This is the point of asking “What is God’s will?” When we ask that question, then take action based on that question, often we and the world itself will be revealed as “bad through and through.”

When we think of voting, we naturally want to ask, “Who is the good person to vote for? How do I do good in voting? How do I be good in voting?” Bonhoeffer would answer, “It’s inappropriate to ask those questions! Instead, you must ask, ‘What is the will of God?’” It’s inappropriate because we are still trying to keep our hands clean. Even when we rattle off the conscience numbing quip, “They’re the lesser of two evils!” we are trying to avoid guilt, but we cannot. As soon as we cast our vote, we’ve incurred guilt. It’s imperative that, as Christians, we do not run from this guilt, but instead willingly embrace it.

Our guilt incurs from actively choosing a person and party who will do bad in the world. When we vote for one party over the other, we are saying “Yes” to all the things that party says yes to, whether we agree with those things or not. We are also saying “No” to all the things they say no to, even if it would be better to say yes to those things. Similarly, we are saying “No” to all the things the other party supports that are in the will of God. This is inescapable and unavoidable. In the end, if we do not embrace this, if we do not willingly take on the guilt of our choices, we become lulled to sleep by the wickedness within our own party of choice, calling good that which Jesus calls evil.

This is how we get things like Christian Nationalism.

Willfully taking on guilt keeps us grounded in reality, reminding us that our politics are not Good (notice the capital “G” there), nor can they make the world Good. There is One who is good though, who is Goodness itself, and that is God, our “Creator, Reconciler, and Redeemer.” It’s that God who has created, reconciled, and redeemed the world to himself in his Son Jesus, and we’re fortunate to have a record of how Jesus lived and what he taught. Doing the will of God means taking on guilt in our actions to follow Jesus’ life and teaching because following Jesus’ life and teaching will require us to take actions in which we take on guilt. Voting according to the will of God might mean you vote against your party of choice, it might mean you vote for someone you don’t like, or voting one way this round and another the next.

Voting is a responsible sin

Because taking action in the world means taking on guilt, how can we know how to act? If it’s all sin, how do we sin boldly while doing the will of God? I point you again, unashamedly, to the teachings of Jesus. When we look at Jesus’ words in Luke 6:27-31, we get a kind of summary of the way Jesus calls us to act.

But I say to you that listen, Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also; and from anyone who takes away your coat do not withhold even your shirt. Give to everyone who begs from you; and if anyone takes away your goods, do not ask for them again. Do to others as you would have them do to you.

In Bonhoeffer’s mind, what Jesus was calling us to in his teachings was responsibility to and for our neighbors for the sake of Jesus Christ. This is what Jesus did in becoming human and living, dying, and rising for our salvation. To live the life of Jesus means to take up our crosses in the daily task of making decisions.

This means that a human being necessarily lives in encounter with other humans beings and that this encounter entails being charged, in ever so many ways, with responsibility for the other human being… Individuals do not act merely for themselves alone; each individual incorporates the selves of several people, perhaps even a very large number. The father of a family, for example, can no longer act as if he were merely an individual. In his own self, he incorporates the selves of those family members for whom he is responsible. Everything he does is determined by this sense of of responsibility. Any attempt to act and live as if he were alone would not only abdicate his responsibility, but also deny at the same time the reality on which his responsibility is based.11

Bonhoeffer uses the example of a father who loves his family by being responsible to and for them, by acting as a part of the ecosystem of the family instead of as a lone individual whose main responsibility is to himself. This would have been a poignant example in 20th century Germany with its high ideals of patriarchy and hierarchy. Even in this enculturated example, though, Bonhoeffer pushes the boundaries of cultural norms. It’s not uncommon in patriarchal societies (like my own Mexican-American one) for fathers to act as the center around which the rest of the family operates. Here, Bonhoeffer says, in the spirit of Jesus’ teachings, that the father must be a positive input into the family ecosystem, not a drain and not a negative input.

In the same spirit, when we go to vote, Jesus is calling us to act responsibly, not in a ambiguous, culturally defined way, meaning not voting for the person or party you think you’re supposed to vote for, but by taking the teachings of Jesus with you into the voting booth and voting according to what you hear Jesus saying. This must be concrete and direct. It’s not enough to say, “A Christian cannot vote for this person,” or “A Christian must vote for that person.” We must vote in the direction that most concretely gives the chance of fulfilling the commands of Jesus.

As has been stated, but which I think bears repeating, to do this means to take on guilt. We must honestly assess the ways our votes contribute to the breaking down of shalom and harmony in our nation and the world. The sins of our parties are our sins, but we willfully take on that guilt in order to live responsibly in the world as disciples of Jesus Christ. Again, Bonhoeffer:

Those who in acting responsibly take on guilt—which is inescapable for any responsible person—place this guilt on themselves, not on someone else; they stand up for it and take responsibility for it. They do so not out of a sacrilegious and reckless belief in their own power, but in the knowledge of being forced into this freedom and of their dependence on grace in its exercise.12

Our political climate and our media thrive on our casting guilt on those of the other party, but Jesus is calling us as his disciples to willingly take on guilt as we cast our votes in the direction of his commandments.

Go, and sin boldly!

It’s important to say that when Bonhoeffer talks about willfully taking on guilt, he doesn’t mean a person should feel shame. The German theological conception of “guilt” was judicial and forensic, not necessarily emotional. We need not feel shame, especially to be eaten up by it, when we vote, but we should reckon with the reality of our political actions. In that way, I think it is appropriate for us to feel the heaviness and sinfulness of our choices. This is crucial, not only to our voting, but to all our actions and decisions, political or otherwise, because without this reckoning, we will seek to justify ourselves, to let ourselves off the hook. This was for Bonhoeffer, and I fully agree, completely antithetical to the Gospel, which reveals that human beings cannot justified by their actions, but only by the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Early on, I decided I could not vote because I could not participate in a sinful system. I abdicated my “right” to have a voice in our government because there was no lesser of two evils. There no righteous decision. Now that I do vote—convinced by Bonhoeffer as I am—I still believe this same thing about our political system. I still believe that to vote is to participate in a sinful system, but now I do it trusting in the forgiving, liberating, and saving grace of the Lord Jesus. Of this kind of willfully-guilty action, Bonhoeffer says, “So Jesus Christ is the one who sets the conscience free for the service of God and neighbor, who sets the conscience free even and especially where a person enters into the community of human guilt.”13

Here, we must take great caution. It would be easy to read this, and to self-righteously justify our normal voting habits. If we do this flippantly, we are not acting “for the service of God and neighbor,” but for ourselves. Remember, we must take the Sermon on the Mount with us into the voting booth. Which people, which party, and which policies follow most the grain of Jesus’ teaching? It’s important that we do this with deep thought and prayer, not basing it on principled ideas of what we think should be, i.e. the idea that Christians must be Republican or must vote Democrat or something like this. We must truly discern with the guidance of the Holy Spirit how to vote, knowing we stand before Jesus as we do.

I have spent many years thinking and praying about what it means to take political action in the United States as Christians. That isn’t to say I am have this figured completely figured out. I don’t. It is to say that I take this all quite seriously, and that I am not flippant in offering this as a faithful way to vote as a Christian. Each election means I have to consciously take this up again, not depending on what I did last time. Each election is a unique season where I must stand before Jesus again and make a choice for the service of God and neighbor, knowing I will incur guilt on myself in doing so. This year, I will cast my votes and then confess to trusted friends how I voted and consciously own the sin I said yes to in doing so, asking forgiveness both from them and from Jesus.

Here, at the end of this post, I am challenging you, Christian voter, to truly consider whether or not your persons and party of choice are following the grain of Jesus’ teaching. Not through principle (i.e. “Christians must vote this way.”), but through an examination of the policies which are supported. I’m challenging you to consciously reckon with the sin you will say yes to when you cast your vote. And I’m challenging you, with the Sermon on the Mount in your heart as you walk into the voting booth on November 5, to sin boldly, trusting in Jesus, not your conscience, to justify you in the end.

This is not unlike what Netanyahu has done with the October 7 massacre.

“The Life Band.” Bound4LIFE. Accessed October 19, 2024. https://www.bound4life.com/the-life-band.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Discipleship DBW Vol 4. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003. Accessed October 22, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central.

The original name of Bonhoeffer’s book, popularly known in English as The Cost of Discipleship, was Nachfolge, again in English, Discipleship, which is the title of the scholarly edition and translation in the Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works in English series published by Fortress Press.

I could add “real” or “true” as an adjective before Christian, as we see antisemitism on the rise again in the United States and the West.

Glenn Stassen in Huber, Ryan. Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s ethics of Formation. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books/Fortress Academic, Lexington Books is an imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc, 2020.

Huber, Ryan. Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s ethics of Formation. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books/Fortress Academic, Lexington Books is an imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc, 2020.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Ethics. Edited by Ilse Tödt and Clifford J. Green. Translated by Reinhard Krauss, Charles C. West, and Douglas W. Stott. Vol. 6. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2009. Emphasis mine.

I understand that many people have felt pushed into a corner because of the uncaring and unwavering political ideologies and talking points of others. I am not addressing that reality in this post, but I know it exists.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Ethics DBW Vol 6. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2008. Accessed October 23, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central. Emphasis mine.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Ethics. Edited by Ilse Tödt and Clifford J. Green. Translated by Reinhard Krauss, Charles C. West, and Douglas W. Stott. Vol. 6. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2009. Emphasis mine.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Ethics. Edited by Ilse Tödt and Clifford J. Green. Translated by Reinhard Krauss, Charles C. West, and Douglas W. Stott. Vol. 6. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2009. Emphasis mine.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. Ethics. Edited by Ilse Tödt and Clifford J. Green. Translated by Reinhard Krauss, Charles C. West, and Douglas W. Stott. Vol. 6. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2009. Emphasis mine.

Also… I’ve recently been reading a lot of Bonhoeffer as well. Reading Letters From Prison for the first time. I love this passage from an essay he wrote describing the 10 years leading up to his imprisonment… When I read it I thought— Damn! Bonhoeffer sees me. Truly a prophet for his generation and beyond.

“One may ask whether there have ever before in human history been people with so little ground under their feet - people to whom every available alternative seemed equally intolerable, re-pugnant, and futile, who looked beyond all these existing alternatives for the source of their strength so entirely in the past or in the future, and who yet, without being dreamers, were able to await the success of their cause so quietly and confidently. Or perhaps one should rather ask whether the responsible thinking people of any generation that stood at a turning-point in history did not feel much as we do, simply because something new was emerging that could not be seen in the existing alternatives.” (from “After Ten Years”)

So little ground under our feet.

I’m grateful, as always, for your thoughtfulness and commitment to honest, prayful, and PUBLIC contemplation. Thank you for writing this, friend.