Where Did The Old Testament Come From?

This History of How the Books of the Old Testament Were Written and How They Became "Scripture."

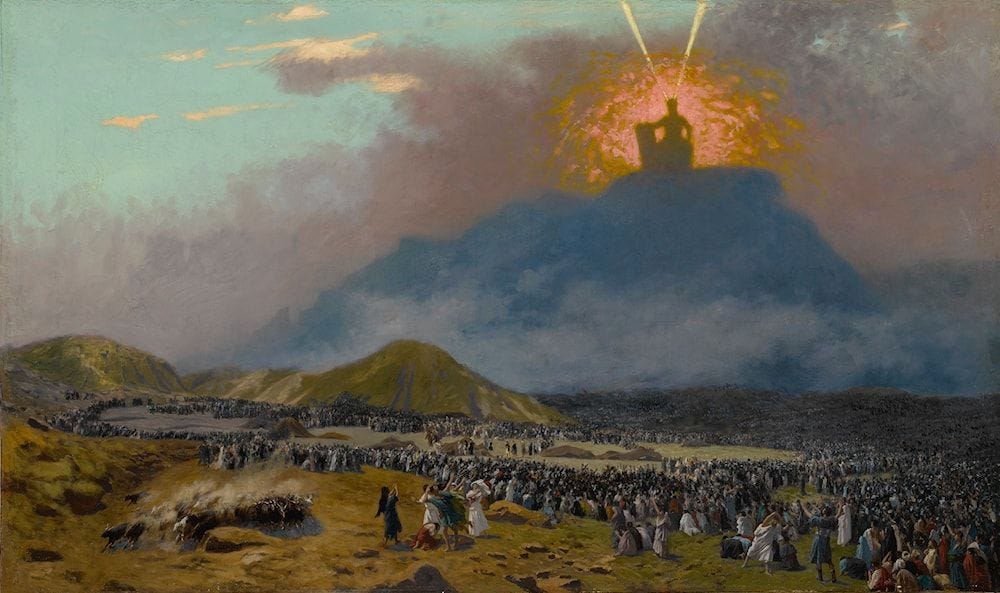

Moses on Mt. Sinai by Jean-Léon Gérôme

The process of “getting” scripture is still largely mysterious to most Christians. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that as most of us are too busy with family, work, and a million other things to take a dive into the long, usually dry, historical work of actually finding out how we got the Bible. Sometimes it’s enough to know we have it, that it’s special, and that God speaks to us through it. There is a beautiful simplicity in that. I’ve had people tell me lately that they don’t really care about “that stuff,” and that’s all well and good, but I love diving into the ins and outs of Scripture, not just what it says but what it is and why it is what it is. I am fascinated by the story behind and underneath that book we call the Bible, or more specifically for our purposes here, the Old Testament. I’m fascinated because there’s so much story in it. Once upon a time, someone picked up a writing utensil for the first time and wrote, “In the beginning, Elohim created the heavens and the earth,” or, “How beloved is your tabernacle, Yahweh of the armies!” or, “The vision of Isaiah, son of Amos, which he saw over Judah and Jerusalem, in the days of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, Hezekiah, kings of Judah.”

There were reasons these words were written, whether to teach, inspire, exhort, or worship, and it’s all that stuff that fascinates me. Not, I should say, at the expense of the text. I don’t value the history and motivation more than I do the text, but it’s important to the way we read and interpret the text that we remember these books didn’t appear out of nowhere. They didn’t fall out of the sky whole and complete. In a way that mirrors the incarnation of Jesus, these works are thoroughly and fully human, and being so, they are thoroughly and fully divine. These are human words, and mystically, they are God’s words. To give one answer to the question, “Where did the OT come from?” we could say, “From ancient Israelites,” and by that we mean people from a long time ago who, for a variety of reasons, sat down and wrote stuff, and now we have the Old Testament.

From There to Here

To give a more researched, academic answer to the question, “Where did the OT come from?” we have to say, “No one really knows.” There are nearly as many opinions as there are Old Testament scholars.1 It used to be widely thought that a council which took place in Jamnia in the late 1st century was convened by Jewish elders to determine the Canon of the Old Testament. The problem is, there’s no real evidence that this council, if it even took place, convened to do that. What seems to have taken place was a discussion about the books that had long been taken for granted as Scripture.2 Something about what Scripture is makes us want to pinpoint a singular moment when “we,” whoever “we” are, said, “Yes, this is it, this is Scripture.” Unfortunately or not, this is not how we figured out what Scripture was, or, for that matter, how it came to us. The same impetus lies behind, I think, the widely false idea that the New Testament Canon was decided at the Council of Nicaea (it wasn’t) and that Emperor Constantine had a hand in decided which books should be in it (he didn’t).

Everything we say about the writing and compiling of what we now call the “Old Testament” is controversial, no matter if you take a conservative view, liberal view, something in between, or something not really on that spectrum at all. I imagine I will go over this in more detail in later posts when I deal with specific parts of the OT, but no matter when the different parts were written, it does seem like there were some final editing passes over the whole work in the post-exilic period, i.e. the time after the Jews returned from Exile in Babylon (c. 538 BC). What this means is that no matter what portions were already written, someone or a group of people went over everything and edited it. Again, there’s a lot of mystery surrounding this, and it’s not really possible to point to a person or group who did this.

It’s hard to go through and detail every opinion of authorship, and some of the theories get very complex, but there are some basic ideas we can take a look at. First, the traditional or conservative view holds that Moses wrote the Torah as we have it, the prophets wrote the Prophetic books which carry their name, every Psalm that names David as author was written by David, and that Samuel wrote 1 Samuel through 2 Kings. It’s a rather straightforward approach. This doesn’t cover every book, but there is some content to leave most of the other books anonymous. Often it is believed that priests wrote the books of Chronicles.

The “scholarly” view, though not very accurately is often associated with being liberal. It generally claims that Moses did not write the Torah, that the Prophetic books, likely stemming from a tradition birthed by the prophet in question, were written by other people than the prophets, even if influenced by the prophets themselves. Anonymity is the key in this view, meaning since there are no claims of authorship in the texts, there is no archaeological evidence of authorship, then no claims of authorship can be made. This view largely claims that the majority of the work, if not all of it, was written, compiled, and edited after the Exile.3 It is granted in this view that much of what was written and edited built upon older traditions maintained by the ancient Hebrew people in either oral form, written form, or both. This is interesting because the idea is that we can sometimes discern (hence compilation and inclusion of) some very ancient texts like the Song of Moses in Exodus 32:1-43 and the Song of Deborah in Judges 5:2-31. Both these hymns are considered to be some of the oldest, original(?) scriptural traditions in the Bible.4

A third view, and the one which I hold, is often called the synthetic view, meaning that the Old Testament is a synthesis of very old material with newer material edited and added onto the old. This is similar to the second view, but lays a special emphasis on the fact that the final form of the OT that we’re all familiar with was built directly upon something older. I tend to think that there are traditions, oral and textual, that go back to the events told in Scripture, and that they’re brought forward, edited, and added to until the post-exilic period when the forms of the books and the OT itself fully accretes into what we recognize as the OT today. For example, I don’t believe the Torah (first five books of the OT) were written by Moses in the form we know them, but that a real man named Moses (yes, the Moses) taught, spoke, and perhaps even wrote something early in Israelite history, and that Mosaic core remains in the Torah as we have it. There are reasons for this, but I’ll leave that for the Torah discussion.

Taking for granted the synthetic view, what we see is a progressive building of revelation within the people of God as different people continue to tell the story of God’s activity in their midst and as they pass down the covenant they were given at Mt. Sinai. The important thing is that God truly revealed himself to the Israelites and that they talked about and wrote about their experience of and encounter with God. Remembrance is crucial to OT faith, remembering what God did for the ancestors and passing the covenant and stories down through the generations.

Hear O Israel, the LORD is our God; the LORD is one. And you shall love the LORD your God with all your heart, with all your life, and with all your might. And these words that I am commanding you today shall be upon your heart. You shall recite them to your children, and you shall speak them when you sit in your homes, and on the road while you walk, and when you lie down, and when you rise up. And you shall bind them as a sign on your hand, and they shall be an emblem between your eyes, and you shall write them on the doorpost of your home and on your gates.

Deuteronomy 6:4-9

In this remembering of how God acted in the past, the Israelites saw how God was moving in their present, throughout and after the exile, and they continued to add to their story, sometimes adding brand new books (e.g. Daniel) or adding material to old books for their new situation (e.g. Deuteronomy 16, where Passover is commanded, but with new directions from Exodus, directions that make sense in their new context).

All of this sounds very human, and so it is. Yet, the amazing thing in all of this is that we believe that in all this speaking and writing and telling of story and teaching of the covenant, the Holy Spirit was at work in every moment, speaking, breathing, and inspiring. To be specific, that means when Moses spoke and wrote, it was under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, and when someone added to the story in the monarchy, it was under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, and when the Exiles carried the stories and covenant into Babylon, it was under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, and when some priests compiled all their material together and edited it into a final work, it was under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. There’s no reason to think that inspiration and the human process are mutually exclusive, in fact, as Christians, this should be the most natural thing for us to believe.

Similar, though not necessarily identical, processes would have happened with other books as well, especially books like the Psalms and the Prophets. Sometime after the exile (I’m hesitant to put a specific date on this), the final edits were completed and nothing more was done. Whatever this process was, it was divinely organic from beginning to end. At some point, the Jewish people, probably unconsciously, concluded there was nothing else to add to these texts. Other texts were being written, and different groups held different books as authoritative, but there was a common consensus across the Jewish world that these 39 books of the OT were inspired and authoritative. This process too would have been subconscious and organic. Over time, these particular stories and books would have distilled through the Jewish world until the 39 books were distinguished among all the others stories which had been told, commands which had been given, and books which had been written. This process of distillation too was inspired by the Holy Spirit.

A Word from God

What I want you to see in all of this is that the Old Testament contains the story of a people who encountered with the living God who created them and the world and that as the people grew and changed, the way God spoke to them grew along with them. It’s not that God changed, but that the people and the context changed, and that God consistently spoke to his people through all those situations. God’s word is present in the text, God is present in the text, but it’s deeper than that. God is present in the story and life of this people, and through the books they passed onto us we learn how to see when and where God is at work in our lives as Christians. More than that, we can have confidence that God is at work even when we’re conscious, or barely conscious of his presence and activity.

Some of these works were likely written in a state of ecstasy (I think of Ezekiel’s visions), and some are the intense and slow labor of a skilled literary craftsman (I think of the Torah), and all of it is the word of God to us. These stories and commands and hymns and prophecies are amazing and terrifying, enrapturing and horrifying, beautiful and confusing, and everything in between. Part of the wonder of the Old Testament, which I’ve stressed and will continue to stress, is just how human it is. There are no niceties here. The passion is high, but so is the violence. The devotion is deep, and so is the judgment. Reading and getting to know the Old Testament has a way of breaking a person out of the dualist trap of the Western mind that values rationality, thought, precision, and disembodiment. And I think that’s exactly what we need right now, in this age of apps and screens, virtual reality and AI. God is in the dirt and the blood, and we’re invited to find him there, both in the writings of the Old Testament and in our own lives.

I’m not, for the record, an Old Testament scholar, but I do have a particular affinity for the Old Testament and as a Christian theologian and ethicist, I rely heavily on the Old Testament.

John Goldingay, An Introduction to the Old Testament: Exploring Text, Approaches and Issues (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2015), 36.

This is where the (in)famous JEDP theory comes in, which applies specifically to Torah. The idea is that four basic sources were compiled after the exile to stitch together what we know as the Bible. J stands for “Yahwist” tradition (J=Y in German), those text wherein the Divine Name “YHWH” is used; E stands for the Elohist tradition, those text that refer to God as “Elohim;” D is the Deuteronomic tradition, which wrote Deuteronomy during and/or after the Babylonian Exile and upon which much of the rest of the OT depends; and P is the Priestly tradition (often broken into subgroups), again post-exilic, who wrote “Priestly” texts like Genesis 1. This is called the “Documentary Theory,” and is a product of German Higher Criticism.

An interesting thought experiment is to take for granted, at least for a moment, that these hymns are the most ancient parts of the Bible, and with that in mind, consider what the most ancient Israelites thought about God. What do the hymns have in common and what are they saying about their God?

“Reading and getting to know the Old Testament has a way of breaking a person out of the dualist trap of the Western mind that values rationality, thought, precision, and disembodiment.” Love that. So true!